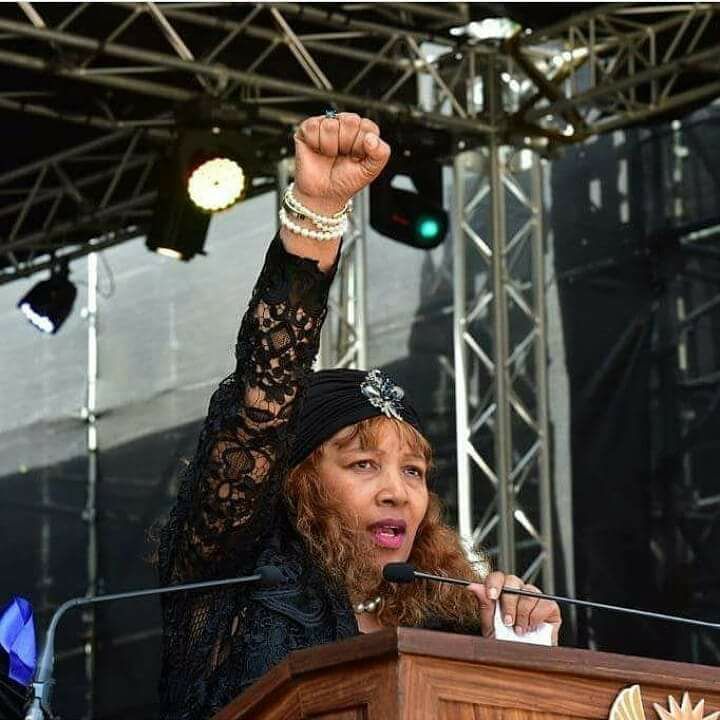

Speech by HRH Zenani Dlamini . Ladies and gentleman, family, friends and all those who’ve travelled from near and afar to be at my mother’s funeral, good morning. Your presence means everything to me and my family. Ever since we announced that my mother had departed this world, we’ve been comforted and strengthened in our hour of grief and weakness by your love, your messages, your visitations, and above all your testimonies of what my mother meant to each of you.

From the afternoon of April the 2nd, when we had to share, even as our hearts were heavy, that we had lost the woman the world knew as Winnie Madikizela Mandela, but who I simply called mum, we have been shielded from our own pain by your love for her.

To those of you who took time to come to Mama’s house to pay your respects, to bring us your condolences: thank you. We have been touched by your humanity. May you do for others what you have done for us.

I stand here this morning to both mourn my mother and also, like you, to celebrate her life. Because hers is one of the most unique stories in recent history. She dared to take on one of the most powerful and evil regimes of the past century, and she triumphed. For those who have not had the time or the courage to go beyond the quick headlines or the rushed profiles, I urge you to search the archives so that you may fully appreciate who my mother really was, and why her life and story matters so much.

One of the most important measures of how someone’s life has been lived is the extent to which they have touched others. By this measure, my mother’s life was a remarkable one. For those of us who’ve been close to her, we have always appreciated just how much she meant to the world. But even we were unprepared for the scale of the outpouring of love and personal testimonies from so many. From the rising generation, which is too young to have been around when my mother took on the Apartheid State, to those who hail from the African Diaspora, we have been reminded of how she touched so many, in ways that are so deeply personal.

As a family we have watched in awe as young women stood up and took a stand of deep solidarity with my mother. I know that she would be very proud of each of you, and grateful for your acts of personal courage: for joining hands in the #IAmWinnie movement, wearing your doeks and bravely mounting a narrative that counters the one that had become, to our profound dismay, my mother’s public story over the last twenty-five years of her life. Like her, you showed that we can be beautiful, powerful and revolutionary—even as we challenge the lies that have been peddled for so long.

As the world—and particularly the media, which is so directly complicit in the smear campaign against my mother—took notice of your acts of resistance, so too did this narrative begin to change. The world saw that a young generation, unafraid of the power of the establishment, was ready to challenge its lies, lies that had become part of my mother’s life. And this was also when we saw so many who had sat on the truth come out one by one, to say that they had known all along that these things that had been said about my mother were not true. And as each of them disavowed these lies, I had to ask myself: ‘Why had they sat on the truth and waited till my mother’s death to tell it?’ It is so disappointing to see how they withheld their words during my mother’s lifetime, knowing very well what they would have meant to her. Only they know why they chose to share the truth with the world after she departed. I think their actions are actions of extreme cruelty, because they robbed my mother of her rightful legacy during her lifetime. It is little comfort to us that they have come out now.

I was particularly angered by the former police commissioner George Fivaz for cruelly only coming out with the truth after my mother’s death.

And to those who’ve vilified my mother through books, on social media and speeches, don’t for a minute think we’ve forgotten. The pain you inflicted on her lives on in us.

Praising her now that she’s gone shows what hypocrites you are. Why did’nt you do the same to any of her male counterparts and remind the world of the many crimes they committed before they were called saints.

Over the past week and a half it’s become clear that South Africa, and indeed the world, holds men and women to different standards of morality. Much of what my mother has been constantly asked to account for is simply ignored when it comes to her male counterparts. And this kind of double standard acts also to obscure the immense contribution of women to the fight for the emancipation of our country from the evil of Apartheid. I say ‘fight’ because the battle for our freedom was not some polite picnic at which you arrived armed with your best behaviour.

The Apartheid state developed a sophisticated and brutal infrastructure for our oppression. It was intolerant of any talk of democracy, especially from a woman activist. I hope that the rediscovery of the truth about my mother helps South Africans come to terms with the pivotal role that she, Winnie Nomzamo Madikizela Mandela, played in freeing us from the shackles of the system of terrorism and white supremacy known as Apartheid.

At my mother’s 80th birthday in September 2016, I said: ‘One day, the story of how you fought back so valiantly against that terrible and powerful regime will be told. Without the distortions.’ It is not two years since I uttered those words and already they’re coming true. Those who notice such things would have realized that her 2013 book, 491 Days—which tells the story of the brutality she experienced at the hands of the Apartheid state, the depths of her despair and her extraordinary resilience and defiance under extreme pressure—was already an invitation for a deep re-evaluation of her life. Because anyone who reads that book grasps just how much my mother dedicated her life to the struggle for a free South Africa.

She made the choice that she would raise two families: her personal family and the larger family that was her beloved country. And to her there was no contradiction in this choice, because she cherished freedom as much as she treasured her family. She was not prepared to choose between the two. She believed it was her calling to defend and protect both from the constant assaults by the Apartheid State.

Five years ago we lost my father and the world descended on South Africa to show its love for him. I truly believe that it is worth repeating that long before it was fashionable to call for Nelson Mandela’s release from Robben Island, it was my mother who kept his memory alive. She kept his name on the lips of the people. Her very appearance—regal, confident, and stylish—angered the Apartheid authorities and galvanized the people. She kept my father’s memory in the people’s hearts.

For those who have wondered, let me assure you that even at the height of her activism, my mother always found a way to let me and my sister know that we were the most special people in her life. When we could not be with her, she wrote letters to us. When we were with her, she did not even have to say anything: her love for us was written on her face. But because she had such a big heart, my mother could also love the community where she lived, no matter where that was. So that when she was banished to Brandfort, she immersed herself in the affairs of this little community and improved the lives of the people, who, in turn, received her with so much love.

In closing, let me say that when you read popular history about the liberation struggle as it currently stands, you can be forgiven for thinking that it was a man’s struggle, and a man’s triumph. Nothing could be further from the truth. My mother is one of the many women who rose against patriarchy, prejudice and the might of a Nuclear-armed state to bring about the peace and democracy we enjoy today.

Every generation is gifted one or two people who shine as brightly as the brightest stars. My sister and I are doubly lucky, in that we got to call Winnie Nomzamo Madikizela Mandela our mother and Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela our father. Unlike many of those who imagine a contested legacy between my father and my mother, we do not have the luxury of such a choice. The two of them were our parents. And all we ask is: no matter how tempting it may be to compare and contrast them, just know that sometimes it is enough to contemplate two historical figures and accept that they complemented each other, far more than any popular narrative might suggest.

I’m deeply grateful to have known and cherished this woman that I called my mother. It is difficult to accept that she is no longer with us. Because she was always so strong. I’m comforted by your presence and your palpable love for this woman we came to know as Winnie Nomzamo Madikizela Mandela. As she said in her lifetime, ‘I am the product of the masses of my country and the product of my enemy.’

May we learn from her and be inspired by her courage.

Thank you.